Campaign through design

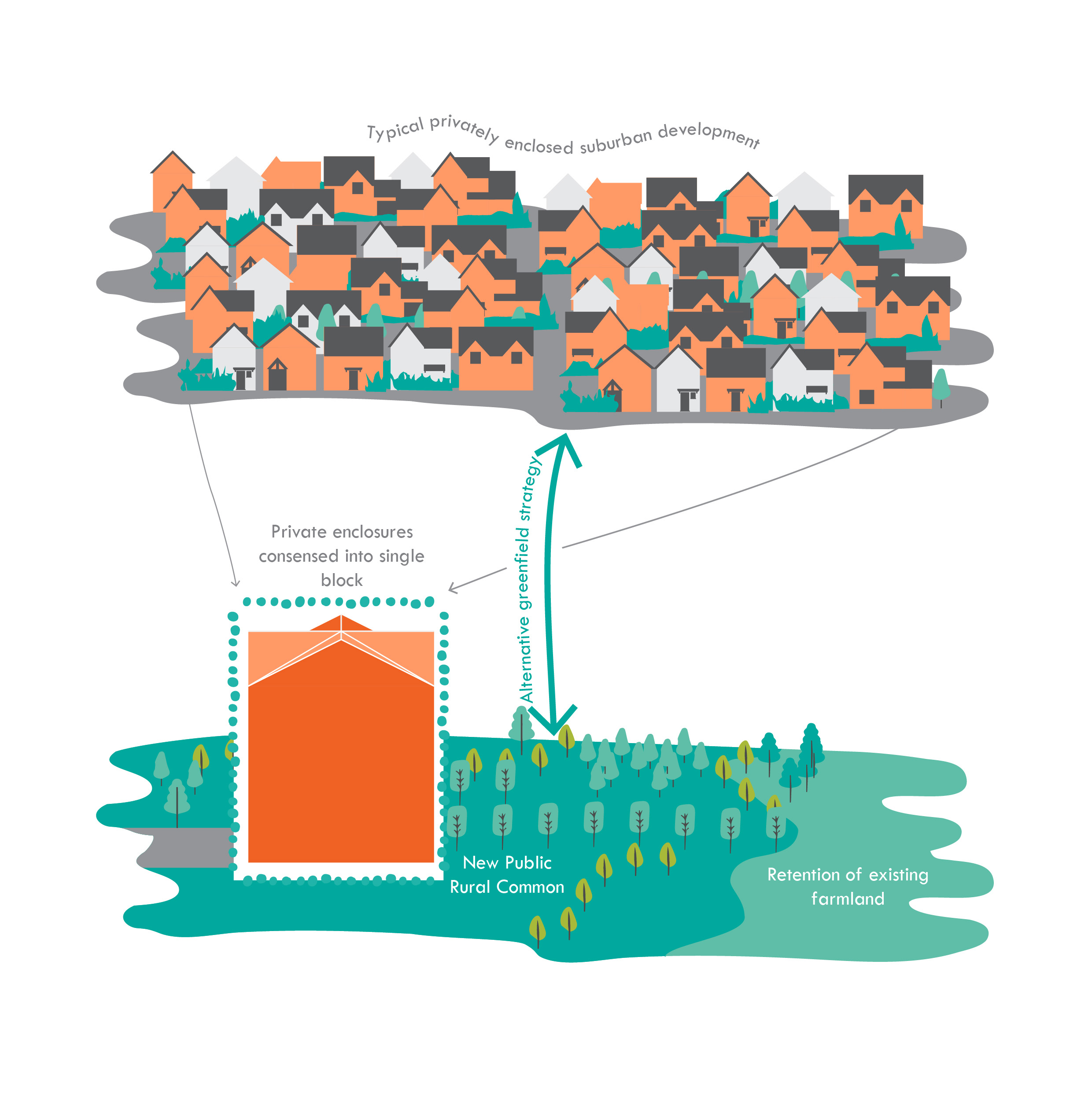

Above: an alternative to the suburbs...

Above: an alternative to the suburbs...

This is the third blog that Ben Nourse, a graduate researcher working with the Cambridge Design Research Studio and studying to become a Master of Architecture in Urban Design, is sharing with CPRE Essex.

Artificial countryside

We must remember that an experience in the English countryside is not an experience with nature. The Domesday Book gives a glimpse into the natural state of Essex: ancient deciduous forest covering the county. Although some woodland remains, notably Epping Forest, since 1086 the majority of Essex has been deforested and enclosed into arable farms. This begs the question: what exactly are we campaigning to protect? Nature, farmland, or anything green in colour? Fundamentally, the countryside is a mufti-faceted landscape. A country golf course, wheatfield and ancient forest can all be classed as ‘greenfield sites’ but have wildly differing ecological values.

In the modern day, the problem continues: farms are being further enclosed into private residential estates. Unfortunately, those on the frontline are losing the fight – the edges of towns are creeping and new low-density towns are being planned. But not all is lost! We can do more than simply campaign against greenfield development. By proposing and advising the type of development the countryside needs, we can directly integrate with the housing conversation. Of course, brownfield sites should be developed first, but it would be naive to assume that all greenfield development is entirely preventable – just look at the fringes of Witham, Colchester or Chelmsford (and, to be honest, most towns in the county). By integrating ourselves with the greenfield development debate, there are more voices to represent the countryside.

So, what should we build? A very big house in the country

The primary issue with the mainstream housebuilding method, particularly in the countryside, is that it is far too low-density. Fundamentally, using less land to house more people by building large blocks means more of the rural landscape is protected. High-density buildings don’t have to look like the concrete tower blocks of the city; rather there is an ideal that already exists in the countryside: the English country house and garden. An example of how far we could push this high-density typology is the Palace of Versailles, which at the peak of Louis XIV’s reign hosted 3,000-10,000 people each day (Titre de L’Encart). For reference, that’s more than the population of Thaxted (2,845 in 2011 census). Look towards Audley End, Highlands Park, Layer Marney, Leez Priory – this is what housebuilding in the countryside could look like!

Of course, the primary difference between what I’m proposing and the country house is the notion of sharing land with many other households, which may be an issue in a national culture of self-ownership. However, the benefits of sharing would result in palatial-scale gardens, retaining the countryside for both the new residents, existing communities and wildlife.